Intro to Put Ratio Options Spreads

Traders use options spreads to reduce risk and costs, generate income, or manage their exposure to underlying price movements and volatility.

Basic spreads are typically created on a ratio of 1:1. A vertical spread has one long option for every short option. A typical straddle or strangle consists of the purchase (or sale) of a call and the purchase (or sale) of an equal number of puts with the same expiration date.

But ratio spreads, as the name implies, don't. And although they come in all shapes and sizes, a good place to begin is with a basic 1:2 put ratio spread (or "one-by-two put spread" in trader-speak).

It's all in the proportions

A standard put ratio spread consists of the purchase of a (long) put option and the sale of twice as many (short) put options. For example, a common 1:2 put options spread includes purchasing an out-of-the-money (OTM) put and selling two OTM puts of a lower strike. Think of it as a put vertical spread with the sale of an extra put at the lower strike. And as we'll see, adding that extra put makes the risk profile look a lot different than a put vertical spread.

In fact, it's sometimes possible to open a put ratio spread for a credit by collecting more on the sale of the two lower-strike puts than is paid to purchase the higher-strike put.

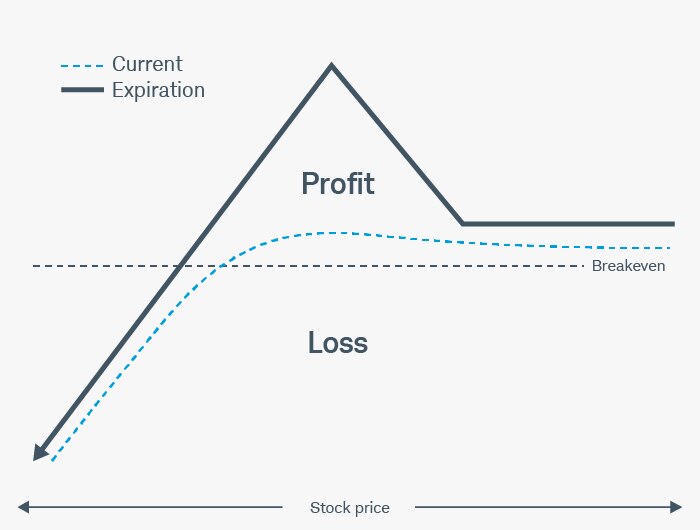

For illustrative purposes only.

Here's one rationale behind the put ratio spread. Suppose a trader has their eye on a certain stock but doesn't want to buy it at the current level, as it looks ripe for a slow drift downward. However, if it falls below a certain price, they would consider buying it.

The put ratio spread risk profile above shows this options strategy is designed for such a scenario. If the stock stays where it is or rises and the options expire worthless, the trader will likely keep the net premium, minus transaction costs. If it drifts down to the short put strike at expiration, the spread reaches the point of maximum profit. If the stock continues down past the short strike at expiration, the trader will likely be left with a long stock position after exercise and assignment.

In other words, with a put ratio spread, the trader better be comfortable buying stock (at that lower strike price) because that's the risk that comes with the strategy. This means that selling the extra put exposes the trader to the risk profile of a long stock position if the stock is below the lower strike and the put is assigned at or before expiration. And like any long stock, the maximum downside risk is the stock falls all the way to zero.

The 1:2 put ratio spread strategy

Say a stock is trading at $71. Using options with 32 days to expiration, a put ratio can be created by buying one 70 put for $6 and selling two 65 puts for $3.50, for a combined net credit of $1 ($6 – $3.50 – $3.50), minus transaction costs.

One way of thinking about this trade is buying a 70-65 put vertical for $2.50 ($6 – $3.50 = $2.50) and collecting $3.50 by selling a 65 put, thus netting the $1 credit.

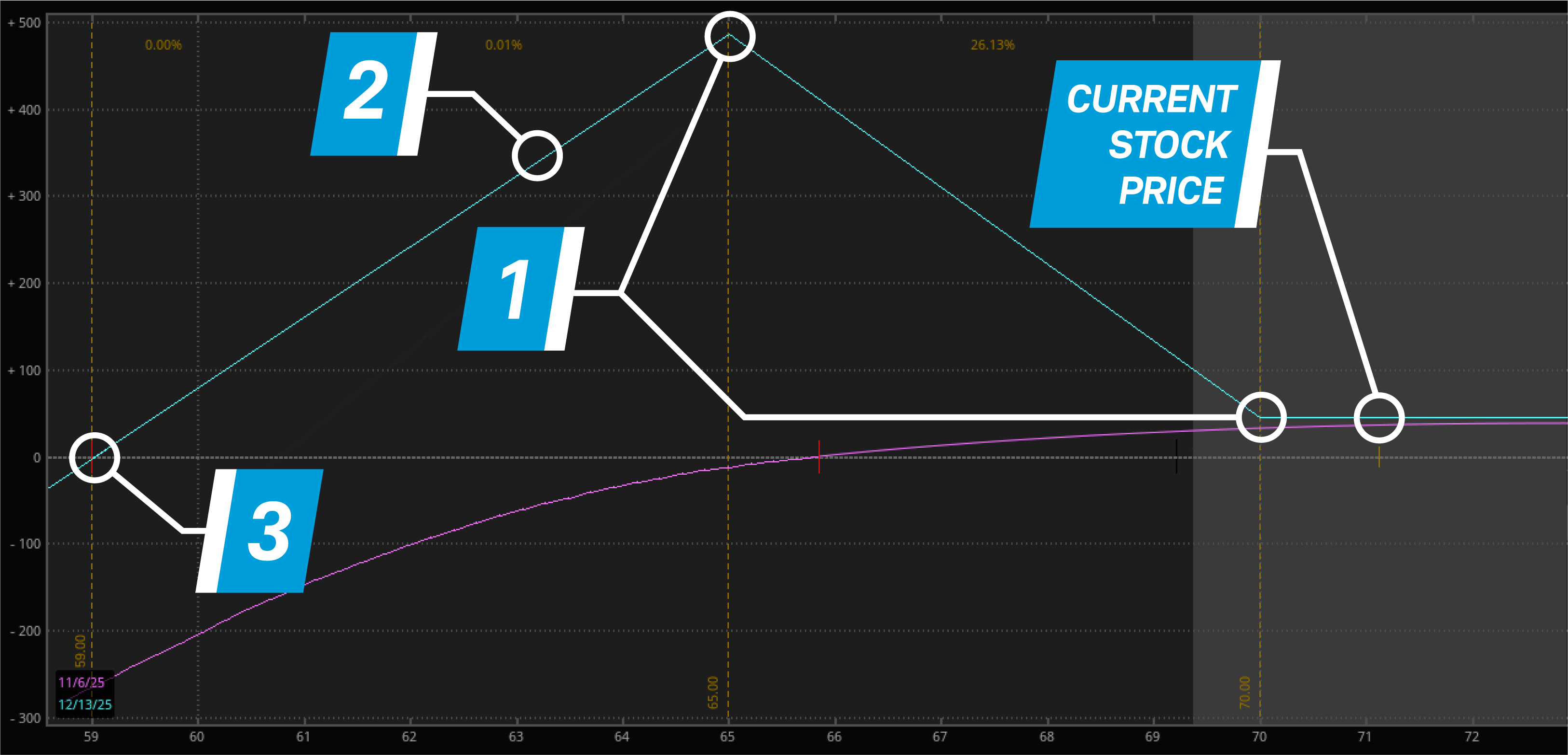

The chart below shows a risk profile of 70-65 1:2 put ratio spread placed for a $1 credit on the thinkorswim® platform, with a break-even price of $59 and a maximum profit at $65.

For illustrative purposes only. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

As shown in the risk profile above (the blue line illustrates the profits and losses at expiration), if the stock falls below $70, the profit on this spread increases all the way down to the $65 level (1), which is when the short strike is at the money (ATM), meaning the stock price equals the strike price. Then the trade starts to give up profits as the stock moves below $65 (2). That is, the losses on the extra short put are beginning to offset the gains in the long put vertical spread, which reaches a maximum at $65 at expiration.

Remember: The put ratio is essentially a long vertical put spread with an extra short put.

Dissecting the trade: How to calculate break-even points

To calculate the break-even point (3), first take the width of the strikes, or $70 – $65 = $5. Then subtract that number from the lower strike of $65 ($65 – $5 = $60). Finally, subtract the $1 credit from selling the spread for a break-even point of $59, excluding transaction costs.

And what if the stock goes up? If the stock holds above $70 (strike price of the long put), all the puts will likely expire worthless, and the trader is left with the $1 credit (which is $100 per spread because the options multiplier is 100), minus transaction costs. This credit is the max gain when the stock holds above $70. The additional short put does not make the trade more bullish.

In general, the higher the implied volatility of the options when initiating the trade, the higher credit received (depending on the strikes selected, of course). When volatility is lower, the opposite will likely be true.

In the example above, if a trader is comfortable taking the risk of buying stock at $65, or about 8.5% lower than its current price, this might be a strategy to consider. In general, when deciding on ratio spread strikes, some traders look for a point where they'd be comfortable buying a stock below the current market price and consider using that price as a short strike. Then, they might choose a long strike that is OTM but closer to ATM. The closer the long strike is to ATM, the less of a net credit (or the higher the debit).

But that's the thing about ratio spreads—it's all proportional.

Putting it all together—with caution

Put ratio spreads can offer traders a way to express a moderately bearish view for relatively low up-front costs or even a net credit. Some traders also use these strategies when they're comfortable owning the underlying position at a lower price but want to collect premiums if it doesn't move sharply.

However, this flexibility comes with serious trade-offs. Consider the following, non-exhaustive list of risks:

- Additional position size risk. Put ratio spreads involve selling multiple puts. If the underlying is at the lower strike at expiration, pin risk exists. This means multiple short puts can be assigned, exposing traders to significant losses if the underlying continues to fall. In a 1:2 put ratio spread, for example, traders may be assigned two short put contracts, leaving them with 200 shares in the underlying.

- Margin pressure. Brokers typically require a high initial margin deposit to open put ratio spreads because the trade involves multiple short puts, which add to the potential overall liability.

- Rising implied volatility. A sudden spike in implied volatility can widen losses for put options spreads. This is because rising implied volatility increases the value of all options, and these strategies involve selling more options than were purchased.

- Early assignment risk. If put ratio options spreads are executed using American-style options, traders can be assigned before expiration on their short puts, exposing them to significant losses.

Traders who are considering using put ratio options spreads should ensure they understand these risks before executing any trade. Still, with careful planning and risk awareness, put ratio options spreads can be a useful tool for qualified traders.