Desert Song: Relying on Alt Data for Economic Pulse

The government shutdown hit its 40th day over the weekend, yet only recently has it had some impact on the stock market (it's tough to isolate factors contributing to the latest market "yips"). But given that third quarter earnings season has been much better than expected, one could surmise that the shutdown is a contributor to increasing angst.

Less dessert, more desert

We all remain in the great government data desert—tumbleweeds where Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) jobs and inflation reports should be—continuing to piece together the economy from private sector thermometers and a few helpful weathervanes. While the shutdown continues to stall many official economic data releases, investors still need a map, so we will triangulate the messages from the latest private readings.

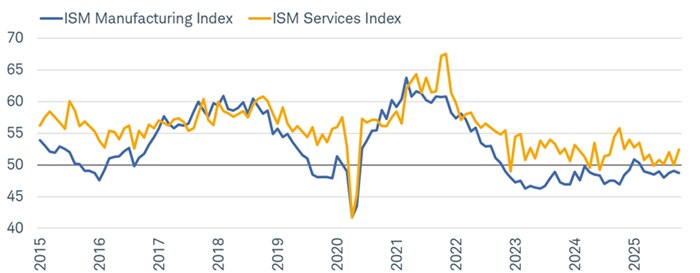

Let's start with purchasing managers' indexes (PMIs). As shown below, the ISM Manufacturing PMI slipped to 48.7 in October, remaining in contraction (defined as below 50). On the other hand, services—still the heavyweight of the U.S. economy—looked healthier. The ISM Services PMI rebounded to 52.4 in October.

Services still outpacing manufacturing

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Institute for Supply Management (ISM), as of 10/31/2025.

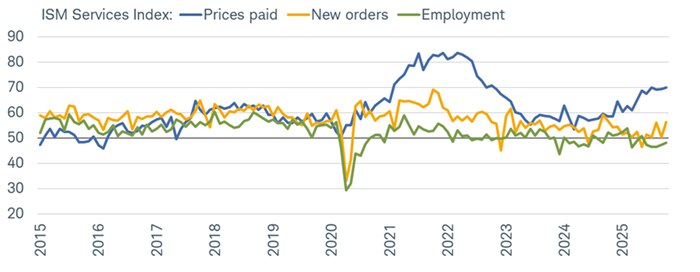

Under the hood is where the story gets meatier when looking at ISMs' prices paid, new orders and employment components, shown below. Within manufacturing, new orders and employment both improved slightly, but remain below 50, while prices paid cooled, but stayed "expansionary" at 58. In lay terms, demand is not rolling over, but it isn't running ahead either; hiring is still cautious; and input costs are rising, just less briskly. That combination reads as a late-cycle grind rather than a cliff dive.

Within services, prices paid hit a hot 70—its first print above 70 since late 2022. And although new orders rose to a perky 56.2, employment remained below 50. Translation: demand is better for services, staffing remains tentative, and service-sector inflation pressure is not quite ready for its curtain call.

Manufacturing's price pressure easing

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Institute for Supply Management (ISM), as of 10/31/2025.

Services' price pressure still firm

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Institute for Supply Management (ISM), as of 10/31/2025.

More on the labor market front

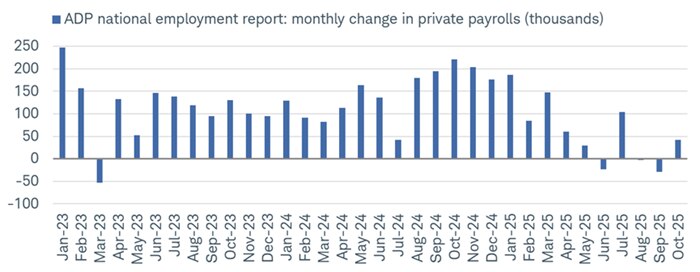

In addition to its monthly readings on job growth, ADP is now offering weekly releases—much needed in light of no BLS-issued monthly jobs reports or weekly unemployment claims at the national level. ADP's National Employment Report showed private-sector payrolls up a modest 42k in October. Although a reversal from the prior two months of negative readings, shown below, it should still be thought of as "still hiring, but pass the decaf."

ADP payroll slump over?

Source: Charles Schwab, ADP Research, Bloomberg, as of 10/31/2025.

By business size, nearly all of the gain in jobs were courtesy of large companies with at least 500 employees. Historically, although ADP hasn't been a perfect preview of the currently missing official BLS payrolls, it's become a useful directional gauge when Washington's lights are off.

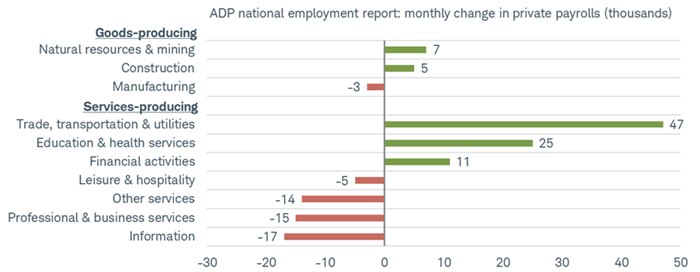

The largest job gains were clustered among the trade/transportation/utilities, education/health services and financial activities, with professional/business services and information on the losing end of the spectrum.

Concentrated job gains in October

Source: Charles Schwab, ADP Research, Bloomberg, as of 10/31/2025.

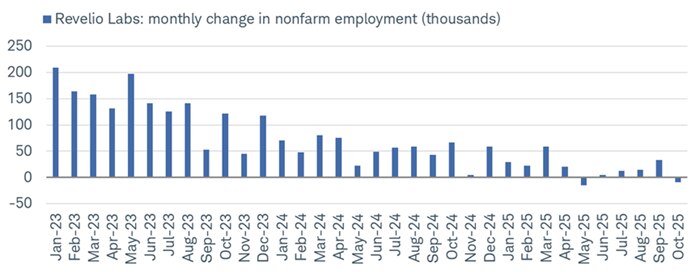

A new entrant into the alternate private data game is Revelio Labs, which stiches together job postings, profiles and employer disclosures. Its latest release, shown below, paints a flatter picture relative to ADP. Revelio's estimate suggests total employment ticked down by more than 9k jobs in October—meaning no growth—and concentrated among government and retail job losses. Revelio also shows job postings down nearly 2%, with weakness broadening in terms of employment sectors.

Revelio Labs employment rolls over

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Revelio Public Labor Statistics (RPLS), as of 10/31/2025.

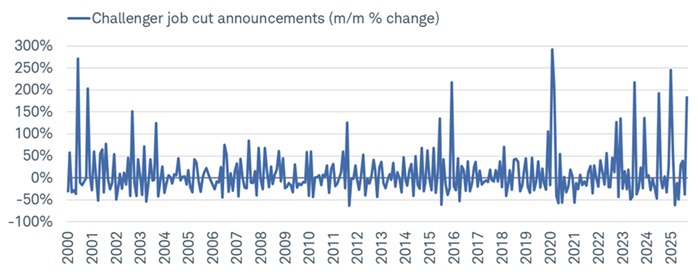

Then there was the sobering view from Challenger, Gray & Christmas. As shown below, announced layoffs spiked by 183% month-over-month to more than 153k in October—the highest for any October in 22 years—bringing year-to-date cuts to more than one million. The private sector (ex-government) series was up by 161% month-over-month to 145k.

The drivers look very 2025: classic cost-cutting with an artificial intelligence (AI) bent—with technology, retail, and logistics prominent on the layoffs list. The primary reason stated for this year's layoffs was tied to AI, cost cutting, and economic uncertainty. Challenger also tracks hiring announcements, with the September-October tallying at more than 400k, the fewest since 2011. Layoff announcements are not the same as realized separations, but they do telegraph business sentiment—and that sentiment looks increasingly defensive.

Layoff announcements spike (again)

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Challenger, Gray & Christmas, as of 10/31/2025.

How do these pieces fit together?

- Growth: Services momentum has reaccelerated, while manufacturing remains soft. That keeps the composite feel of the economy in "slow expansion," not recession. If this were a road trip, the service side just merged back into the right lane, while factories are still at the rest stop checking the map.

- Inflation mix: Manufacturing prices paid cooled from September, but stayed expansionary, while services prices were uncomfortably hot. That split—goods disinflation vs. sticky services inflation—never fully went away and may complicate any "mission accomplished" narrative on inflation.

- Labor demand: ADP says hiring continued, but barely; Revelio suggests essentially flat employment and fewer postings; Challenger shows companies actively sharpening the cost pencil via layoff plans. Put together, labor demand is normalizing from too hot to tepid, with growing pockets of outright weakness. In terms of Federal Reserve policy, this may be a comfortable enough mix—cooler, not frozen— to keep monetary policy on hold near-term, even if it's arrived via an unhelpful data blackout. In fact, the Fed may not receive official data for October and November prior to the December Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, also arguing for a considered pause.

- Confidence and capex: The soft manufacturing employment index, persistent contraction in new orders, and the run-up in layoff announcements argue that managers remain in "optimize" mode—sweating utilization and margins rather than green-lighting big new rounds of hiring. Services companies did report better activity and orders, which should cushion growth; but the sub-50 employment reading hints that many are meeting demand with productivity and scheduling tweaks, not headcount.

What say you, consumer?

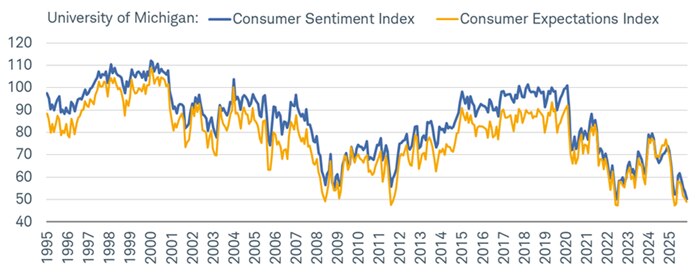

The lack of federal data means we also have an impaired view of the U.S. consumer—at least as it pertains to income growth, savings rates, and spending. In the meantime, sentiment data continue to point toward a mostly anxious and perhaps even depressed consumer base. As shown below, the Consumer Sentiment Index from the University of Michigan (UMich) fell in November to its lowest since June 2022. Other than that month, the index is at its lowest in history. The expectations component, which tracks how consumers feel about the economic outlook, also fell and is nearing a cycle low.

Sentiment rolling over (again)

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 11/7/2025.

One of the decisive drivers of weaker sentiment in the post-pandemic era has been elevated inflation expectations—largely driven by the fact that price levels have not come down to where they were before 2020. As we have noted before, the likelihood of that happening is slim, and if that did occur, it would likely coincide with a major recession. Despite inflation indexes' rates of change easing over the past few years, though, consumers don't feel much better about it, evidenced by the chart below.

Inflation on the brain

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 11/7/2025.

Forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only, may be based upon proprietary research and are developed through analysis of historical public data.

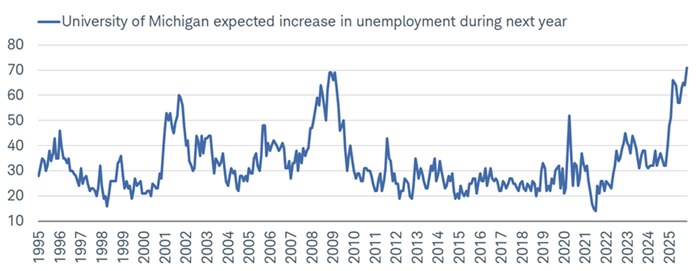

Inflation isn't the only anxiety-inducing factor, though. One of the more striking developments in the November UMich survey was the spike in the percentage of individuals expecting a higher unemployment rate a year from now. As you can see in the chart below, the share is now higher than where it was during the depths of the global financial crisis, and it's just shy of an all-time high.

Labor also on the brain

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 11/7/2025.

Forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only, may be based upon proprietary research and are developed through analysis of historical public data.

It's worth noting (and admitting) that consumer sentiment data have not been accurate predictors of spending in the post-pandemic cycle. Much of that is due to the fact that despite angst over inflation and the labor market, the U.S. economy has not experienced a full-blown layoff cycle in the past five years. What seems to be the new normal is—to build on our friend Kyla Scanlon's coining of the term "vibecession"—something akin to a "vibepression" (persistently abysmal vibes yet still-resilient spending).

In sum

So, what's the punchline in this data desert standup routine? Even without the usual government stats, the private gauges of activity rhyme: overall growth is lukewarm, the goods side of the economy is slogging, services have a decent pulse, labor demand is cooler, consumer sentiment is dire, and prices heat is now concentrated in services.

It's an economy that looks less like a cliff and more like a long, slightly uphill treadmill—hard work, limited scenery, and the occasional splash of energy drink from better services data. When official releases return—or better said, when official releases have "clean" data once again—it will not surprise us if they broadly confirm this "slowish expansion with softer labor demand and sticky services prices" script. Until then, we'll keep following the private breadcrumbs—and yes, we brought extra water.