SPACs: What Investors Should Know Now

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) have been around for decades, functioning as vehicles for bringing companies public. Until 2020, SPACs—also known as blank-check companies—weren’t nearly as popular or common as the traditional initial public offering (IPO) process. Yet, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—which ushered in an influx of new retail traders and investors, along with the unearthing of several speculative segments of the market—SPACs gained immense popularity.

Despite a boom-bust cycle already having played out in terms of SPAC issuance, investors are still left with several questions regarding them, not least being details around historical performance and potential risks. They are incredibly complex vehicles and differ widely in size, structure, and quality.

A faster track to public markets

SPACs generally offer a less arduous path for companies that wish to go public. They are created by a sponsor—ranging from a private equity firm to a former corporate executive—who works with an underwriter to bring the blank-check company public. Money is raised in a public stock offering and the SPAC trades on an exchange with the intent of finding a target company with which to merge. If and when a merger is completed, the SPAC takes the identity and ticker of the target company.

One of the main advantages for target companies—and effectively, SPACs—is the ability to talk about the future and make predictions, which is prohibited in the traditional IPO process. That is a particularly attractive proposition for SPACs that are hunting for innovators and disruptors. Also of interest to target companies is the lack of necessity for roadshows (a key part of the traditional IPO process), which typically consist of several meetings with institutional investors and are meant to secure capital. With SPACs, capital is already raised by a sponsor in one vehicle, making the match process with a target company a bit easier.

For the individual investor, SPACs offer a direct opportunity for access to new companies—which has historically been reserved for larger institutions and hedge funds. There is also an attractive affordability trait. In most cases, investors can purchase one unit of a blank-check firm for $10, which consists of a common share and a fraction of a warrant (which gives the right to buy more shares at a specified price in the future). The capital aggregated by the SPAC is invested in Treasury bills until a target company is found, by which time it is deployed to complete the merger process.

Fee structures vary but, in general, the sponsor’s equity stake amounts to 20%; so, after banking fees, the cost to public investors at the time of the SPAC’s IPO, and/or merger with a target company, there are many times when the costs associated with SPACs can be much higher than traditional IPOs.

Measuring risk

Despite offering a more efficient route to public markets, SPACs still carry a set of risks that investors should be aware of. Many have experienced significant bouts of volatility throughout their lifespans, with much stemming from excitement over a sponsor (be it a celebrity or well-known private equity firm), or hype over a potential merger. In both cases, some SPACs have seen their share prices triple in value in a matter of days or weeks, only to swiftly fall back to—or, in some cases, below—their IPO prices.

Rapid and large price swings warrant an extra degree of caution because of the lack of information associated with SPACs. Given they are purely aggregators of cash, price action cannot be tied to any fundamentals (such as earnings streams) until a merger is completed. This is one of the key reasons several SPACs have seen deteriorating performance, and reinforces the importance of performing due diligence on sponsors and the target industry of interest.

Another risk worth considering is a SPAC’s failure to fulfill its goal of finding a merger target—forcing it to liquidate. In general, SPACs have two years to complete a merger; if they don’t, they liquidate and investors get their pro-rata share of the aggregate value of the SPAC. Though this isn’t as much of an acute risk at the present moment, it’s worth watching in 2022, given many SPACs that launched in the fall of 2020 will be approaching their two-year deadlines.

Lastly, the regulatory environment may pose some challenges in the future. With the pickup in speculative trading activity over the past year, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has sharpened its focus on SPACs. SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has been vocal about the need to potentially revise rules and disclosures, which may force existing firms to make structural adjustments, and may alter the processes for future deals. To some extent, this has already affected the SPAC market. An April 2021 report from the SEC hinted at changing the way warrants are accounted for—as liabilities vs. equities. That alone pushed over 100 SPACs to restate past financial statements and caused a sharp pause in new issuance.

Measuring performance

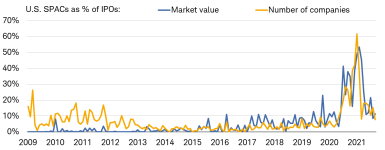

In addition to risks, central to investors’ focus is SPACs’ performance. As mentioned earlier, a boom-bust scenario has already occurred for issuance. SPACs surged in popularity in 2020—and given the rash of issuance, so did their share of overall IPO activity (both in terms of total deal value and the number of companies), as you can see in the chart below. By February 2021—the peak in activity—SPAC value accounted for over half of overall IPO value in the United States.

The SPAC boom has faded

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 9/30/2021.

Performance has largely followed the path of issuance activity. For myriad reasons, several speculative pockets of the market gained steam in the latter half of 2020—not least because of the ample liquidity environment (courtesy of both fiscal and monetary aid) in the wake of the pandemic, heightened interest in day trading, and incredibly swift recovery in stocks from the S&P 500’s low on March 23rd, 2020.

Looking at performance since the beginning of fall 2020 (when many frothy segments of the market started to rally), SPACs across the board—measured by the ISPAC Index—gained more than 30% by February. Even more impressive was the gain for SPACs with deals announced, which climbed above 80%. As you can see in the next chart, though, the peak in the frenzy looks to be behind us, as gains have completely faded for the ISPAC Index. While firms with deals announced have fared better in a relative sense over the past year, performance has been anemic since March 2021.

Performance has been lackluster since March

Source: Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 10/12/2021. All three indices indexed to 100 at 10/2/2020. ISPAC Index is a passive rules-based index that tracks the performance of the newly listed Special Purpose Acquisitions Corporations ex-warrant and initial public offerings derived from SPACs. SPACs Without Deals Index is an equal-weighted index, consisting of 65 SPACs that have separated, but have not completed a business combination. Constituents trade as common stock, warrants, and units. SPACs Deal Announced Index is an equal-weighted index, consisting of 66 SPACs that have announced, but not completed, a business combination. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Traditional IPO performance is a bit more difficult to track over time, given the massive number of companies that have gone the standard route. Yet one can look to the Renaissance IPO Index, which measures performance of newer IPOs and dates back to 2009. Returns have been impressive, as the index has gained over 600% since its inception. However, the run has not been uninterrupted by volatility, as evidenced by sharp drawdowns in 2015-2016 (-36%), 2020 (-38%), and 2021 (-29%).

Conclusion

The speculative exuberance phase for SPACs looks to have ended, but that doesn’t discount the reality that many are still active in their search for target companies. Given the playing field is still flooded with pursuant SPACs and demand for targets remains strong, key to watch will be the sustainability and longevity of merger activity. The severe drop in overall performance since the beginning of 2021 shows investors are no longer willing to pay sky-high premiums, and the meager performance of SPACs with deals announced this year suggests that hype around deal activity has faded.

Even though both deal activity and performance for SPACs have fallen considerably, interest among investors remains high. Moments of truth are likely to emerge in the coming year for several companies that are still aiming to find merger targets. As with any investment, risks associated with those SPACs—and the broader segment—should be carefully analyzed.