Inflation: Persistently Transitory

Key Points

Persistently going from one transitory source of inflation to the next may keep inflation elevated for longer than markets currently anticipate.

A rising number of labor strikes hint that workers demanding higher wages could be a next source of inflationary pressure, following the transitory effects of supply shortages and soaring energy prices.

The lift to earnings from inflation may more than offset any compression on stock valuations from any tightening of financial conditions, given the more relaxed inflation mandates of central banks.

If the global economy persistently goes from one transitory source of inflation to the next, it may keep inflation elevated for longer than markets currently anticipate. Following this year’s supply disruptions and recent climb in energy prices, markets may begin to price another potential source of inflation: workers demanding higher wages as strikes blanket the news. Yet, central banks’ attitude toward inflation has changed. This may mean that the lift to earnings from inflation could more than offset any compression on stock valuations from tighter financial conditions.

Supply chain problems may have peaked

It’s a simple law of economics: prices rise when supply cannot meet demand. This year’s post-lockdown re-openings led to a surge in demand, which suppliers have had trouble meeting. Although demand can snap back quickly, supply often takes time to get back up to speed. Bottlenecks at ports have contributed to the shortages. The resurgence of port traffic in August and September led to unprecedented logjams and delays.

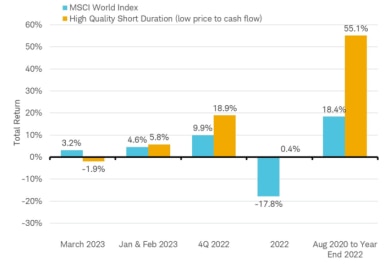

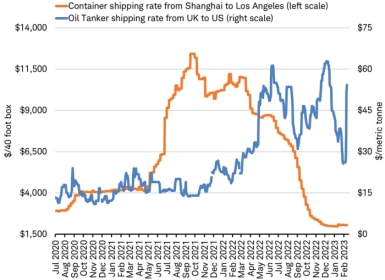

While supply shortages pose a risk to third quarter earnings reports which begin this week, they may finally begin to ease now that we are past the seasonal peak in shipping demand. The number of ships waiting at anchor to unload at the U.S.’s busiest ports (Los Angeles and Long Beach) appears to have peaked on September 19, according to data from the Marine Exchange of Southern California. The cost to ship a 40-foot container unit from Shanghai to Los Angeles (the world’s busiest route) is tracking last year’s pattern (though at higher levels) and is now past its peak of a few weeks ago.

Shipping costs echoing last year’s pattern

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/9/2021.

Supplier delivery times are no longer worsening according to surveys of purchasing managers, suggesting this transitory factor driving inflation may have peaked. However, it could take a long time for delivery times to return to normal.

But energy prices have surged

Rising energy prices, including natural gas and coal, are likely to drive up electricity prices this winter. This is the latest transitory thrust of inflation and may shift the price pressure from goods to services. Energy prices have already surged, as you can see in the chart of U.S. CPI below, but the rise may have further to go.

Energy prices lifting inflation

Source: Charles Schwab, Bureau of Labor Statistics August Consumer Price Index data as of 10/9/2021.

In Europe, spending on natural gas, electricity and heat energy make up a little over 5% of consumer budgets. In September those prices rose 17% from a year ago, unexpectedly lifting inflation in the Eurozone to the highest level in 13 years.

Because natural gas prices are greatly affected by weather-driven demand, they are difficult to forecast. Exactly how much of the rise in wholesale gas prices will be passed through to consumers is uncertain. Other countries may follow France, which has announced a freeze on natural gas and electricity prices going into the winter months.

Are wages next?

Could workers demanding higher wages be the next source of inflationary pressure? Recent headlines touting big union pay demands and strike announcements may seem to echo the hyper-inflationary 1970s. In the first week of October, U.S. strikes included nurses in Massachusetts; steelworkers in West Virginia; school bus drivers in Maryland; service workers in Colorado and workers at Kellogg plants in Nebraska, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. The big headline looming is a potential Hollywood strike of nearly 60,000 film and television crews. Every local newspaper in America is covering a seemingly widening rash of strikes.

Yet, these strikes are unlikely to reach the same intensity or have a similar impact on wages as those of the 1970s. In fact, there have been very few significant strikes this year, according to the U.S. government’s official definition (involving 1,000 or more workers and lasting one full shift or longer). With only 11 strikes this year that meet the minimum requirements to be tracked, the charts below show how the trend in striking workers is far from that of the 1970s in the U.S. and United Kingdom. Similar patterns for strikes are seen in Canada, Germany and other major countries.

Strikes unlikely to match those of the inflationary 1970s

*U.S. strikes tally includes only those involving 1,000 or more workers and lasting one full shift or longer. Source: Charles Schwab, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Office for National Statistics latest data as of 10/9/2021.

Major economies have seen a steady rise in part-time workers in recent decades, accelerated recently by the rise of apps enabling “gig” working. This tends to limit labor price increases. The shift to working from home, accelerated by the pandemic, also has the potential to limit wage increases by enabling firms in high-cost major metro areas to hire from a much broader and less costly pool of labor.

Where wages are indexed to inflation, we do not see outsized increases. A 1.6% raise to the minimum wage in Spain in September and a 2.2% rise in the French minimum wage beginning in October serve as recent examples, tempering this next transitory driver of inflation and its impact on corporate profit margins.

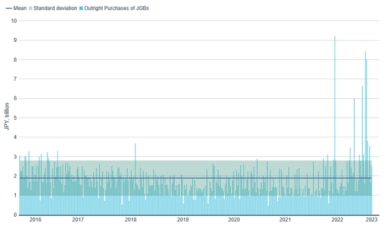

Central banks aren’t that worried

Even if wage pressures do end up extending the climb of inflation, central banks may not act aggressively to tighten financial conditions. Major central banks have relaxed their commitment to fighting inflation and prioritized supporting employment in recent years.

- The U.S. Federal Reserve shifted to an average inflation target last year, allowing inflation to “moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.” It has also changed the full employment part of its mandate, targeting “shortfalls” from full employment, meaning it will no longer tighten policy because the labor market is strong.

- The European Central Bank has shifted to a symmetric 2% target as opposed to its previously stated “close to, but below 2%” target, as well as allowing for a temporary overshoot of inflation.

- The Bank of Japan several years ago raised its inflation target to 2%, stressing that it would be comfortable with an overshoot. Inflation has averaged just 0.5% over the past 35 years.

This means potential tightening by central banks may be much more muted than in the past, even if inflation persists longer than they currently anticipate. Subsequently, the downward pressure on price-to-earnings ratios from tighter financial conditions may be relatively small, as has been the case so far in 2021.

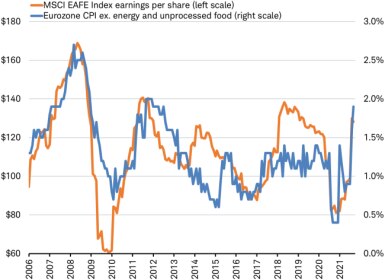

Inflation lifts earnings

Impacts on global stock market returns from potentially mild downward pressure on price-to-earnings ratios may be more than offset by the upward lift to earnings provided by inflation.

While higher energy costs may act as a drag on the economy and households, they also have a history of boosting overall earnings for the major indexes, due to energy companies’ outsized contribution to revenue and earnings. For example, although Energy stocks make up 4.5% of the overall market capitalization of the European STOXX 600 Index, those companies are expected to contribute 13.8% of overall revenues to the index in 2021, according to Refinitiv.

Inflation and earnings

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 10/8/2021.

Persistent inflation

Looking ahead, new sources of inflation may continue to arise. Unless the mounting pressures push inflation to significantly higher levels that would provoke central banks into aggressive tightening, the impact on global stock markets may be a positive.

Michelle Gibley, CFA®, Director of International Research, and Heather O’Leary, Senior Global Investment Research Analyst, contributed to this report.